January

08

January

08

Tags

Top 10 Homes in Middle-Grade Fiction by Keir Graff

Homes are important in kids’ books, probably because visiting other people’s houses awakens our first wonderings about how other people live—and, by inference, how we might live once we get to make decisions about such things. (Imagining others’ circumstances also has a lot to do with the development of empathy, too.) I’ve spent a lot of time lately talking about the real-life inspirations for my new middle-grade novel, The Matchstick Castle, which had its genesis in my notion of writing a story in which a house was a character. Strangely, it only recently occurred to me to think about the fictional houses that wormed their way into my imagination—or maybe it was the other way around. Please note that this is my top 10, not a claim to being THE top 10, and, with only a couple of exceptions, reflects my 1970s childhood and the titles that were widely read and taught at that time.

Badger’s House in The Wind and the Willows

When Mole and Rat, lost and freezing in the snowy Wild Wood, trip over a door-scraper, Mole fails to see its significance. Rat, however, understands that door-scrapers mean doors, and with enough digging uncovers a doormat and then a door: Badger’s. I know readers who detest the whole anthropomorphic-animal genre and believe animals should never wear waistcoats, but to me, the fortuitous discovery of Badger’s cozy, enticing home is nothing short of magical. (And I would be very surprised if one Mr. Tolkien didn’t feel exactly the same way.) Badger’s home, with its branching passageways and fire-lit kitchen, somehow manages to be vast and mysterious, and warm and cozy, all at once.

Bag End in The Hobbit

Is there a more influential fantasy novel? All I know is that, once my dad started reading it to my brother and me, we were so impatient with his pace that we took over and soon had finished not only The Hobbit, but the whole Lord of the Rings trilogy as well. (And then all I wanted to read were books that were very much like them, something Terry Brooks and a host of other authors were only too happy to provide.) Part of Tolkien’s genius is that he knows children will intuitively identify with the smallest characters, the hobbits, and, like Bilbo, kids can only take so much adventure before they want to return to their own safe and cozy hobbit-holes.

The Burrow in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

The Burrow, where the Weasley family lives, is not underground, as its name suggests. And, I confess, the Harry Potter films have contaminated my imagining of it in a way that other films of other books been unable to do. But the idea of a cluttered, crowded house that started as a pigpen and is “so crooked it looked as though it were held up by magic” (which it is), is, for lack of a better word, enchanting. Even better is the family inside, a big, welcoming, warm-hearted brood perfectly suited to their environs. The best kid-lit homes are extensions of their occupants’ personalities, and it’s truly impossible to imagine the Weasleys in, say, a house on Privet Lane.

The Caravan in Danny, The Champion of the World

Danny is my favorite of Dahl’s books, because it balances his trademark wackiness and cruel characters with genuine warmth, offering character development alongside some class commentary that even a kid can understand. The warm bond between Danny and his father is set up early on, and the description of their stationary wooden caravan is essential to that. It is a small and humble home but safe, cozy, and appealingly self-contained. The outhouse out back (in winter, it’s “like sitting in an icebox”) is the kind of detail that makes Danny’s circumstances perfectly clear and the apples that thump down on the roof in the night add a wonderful reminder of the world outside.

Howl’s Castle in Howl’s Moving Castle

I’m no expert on folklore, but it seems like Diana Wynne Jones must be playing on Baba Yaga’s chicken-legged hut; still, turning a hut into a castle that billows black smoke is an impressive innovation. Though the castle scares the townsfolk of Market Chipping, in the land of Ingary, hatmaker Sophie isn’t particularly frightened. The Witch of the Waste has turned her into an old crone and, caught in the open at night, she’s getting cold. When the castle rumbles toward her, she decides that its smoke signals a warm hearth inside and hails it like a taxi—it obediently stops. Howl’s Moving Castle is a wonderful work of imagination, and if you haven’t seen it brought to life through Hayao Miyazaki’s animation, do it: you’re in for a treat.

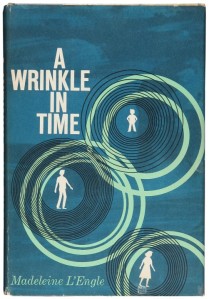

The Murry House in A Wrinkle in Time

L’Engle doesn’t give us a grand overview of Meg Murry’s home but offers plenty of tantalizing details: it’s almost two hundred years old, it’s on a hill nearly four miles from town, it has a forest behind, an orchard nearby, and a tree in which her twin brothers have built a tree fort. Even better, because she’s oldest, Meg’s bedroom is in the attic (although she’s sometimes scared to be alone up there) and her scientist mom has a lab off the kitchen (where she sometimes cooks up dinner along with her experiments). But best of all is the “pleasant, if shabby” house’s vibe, one of my favorite things about the book: it’s a place where midnight visitors are treated with unflappable courtesy and where remarkable things are accepted with perfect equanimity.

100 High Street, in The House with a Clock in Its Walls

When recently orphaned ten-year-old Lewis Barnavelt is sent to live with his Uncle Jonathan—whom he’s never met in his life—in New Zebedee, Michigan, he is delighted to discover his uncle lives in a hilltop mansion that is as fascinating as it is odd. Ancient coins, stained-glass windows, a secret passage behind a bookcase—and, best of all, Uncle Jonathan is a warlock and his neighbor, Mrs. Zimmermann, is a witch. But why does Uncle Jonathan want to stop the clocks at night? It turns out that Uncle Jonathan hasn’t owned the house for long, and the weird and wonderful mansion holds a potentially world-ending secret within. This might be my favorite haunted-house story because the house is both warm and scary, which is harder to write than it seems.

The Professor’s House in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe

This choice may strike you as perverse, given that Narnia, and not the old Professor’s house, is the entire attraction here. Yet Lewis’s efficient scene-setting should not be underestimated: in just a few brief pages the Pevensie kids arrive in the country from air-raid-wary London, to the kind of house you dream of exploring and under the care of a kindly but distant old man. (“We’ve fallen on our feet and no mistake,” declares Peter.) In effect, this is the kind of house in which a magically transporting wardrobe seems possible, maybe even probable. And even if you think I’m just choosing this house for one piece of enchanted furniture, I can live with that, too.

Sam’s Tree in My Side of the Mountain

When we were kids, my big brother and I spent much of our time planning to run away from home. We had a perfectly good house to live in, and kind, loving parents, but running away from home is something all kids consider at least once because they crave independence and adventure. Conveniently, we lived next to a mountain in Montana, so when we encountered Jean Craighead George’s classic tale of self-reliance and survival—the Hatchet of its time—we were smitten and naturally wanted to find our side of the mountain. I fear the pace and the documentary-style naturalism makes this lost to today’s kids, but perhaps, if they read the first few pages and fall in love with Sam Gribley’s cozy hollowed-out tree, they too will wonder what it might be like to be at home in the woods.

Sunset Towers, The Westing Game

First of all, apartment buildings are somewhat rare in children’s literature. Even rarer are apartment buildings filled with the kind of oddball characters only Raskin can create. Her puzzle-books aren’t for every reader (although I hope every young reader at least gives them a chance). As for me, the “glittery, glassy apartment house” that stands alone on the Lake Michigan shore is like a three-dimensional game of Clue, only infinitely more surprising. The first page alone is full of so many irresistible contradictions that who can resist reading more? (The Westing House is pretty interesting, too, but when I was a kid I found the idea of living in an apartment infinitely more interesting—probably because I lived in a house.)

Keir Graff is the author of two middle-grade novels, including the The Matchstick Castle, published in January by G. P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers and Listening Library. Since 2011, he has been cohost of Publishing Cocktails, an occasional literary gathering in Chicago. By day, he is the executive editor of Booklist. You can find him on Twitter (@KeirGraff), Facebook (Keir.Graff.Author), and at www.keirgraff.com.

Keir Graff is the author of two middle-grade novels, including the The Matchstick Castle, published in January by G. P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers and Listening Library. Since 2011, he has been cohost of Publishing Cocktails, an occasional literary gathering in Chicago. By day, he is the executive editor of Booklist. You can find him on Twitter (@KeirGraff), Facebook (Keir.Graff.Author), and at www.keirgraff.com.

There are many on this list I have never read, but when I saw the title of the post I immediately thought of the Burrow. I love the Weasley family and all that they represent, both in fiction and reality ❤

Looking forward to reading your book!

Reblogged this on Meghan Marentette and commented:

It’s true, a well-imagined setting can make a story pitch a tent in your heart forever. I’ve read many of these books in Graff’s top ten list of middle grade books with memorable home settings, and I can attest to the influence they have had on me as an author. Settings are sometimes my favourite bits to write. Enjoy!

What a great idea for a top ten and I love your choices. In fact, when I went to C.S. Lewis’s actual house outside of Oxford, I couldn’t help being a little disappointed because it was so ordinary compared with how I had imagined the professor’s house.

Yes to all your houses! These homes were all so amazing in their own way. I wanted to live in each one of them.

Thank you, all! Glad this list struck a chord. It was a lot of fun deciding which ones to include.

The Hobbit, Harry Potter, The lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, and A Wrinkle in Time we’re some of my all time favorites in elementary and middle school. I still re-read the Harry Potter and LOTRs series from time to time.

Rereading The Westing Game for the third time right this minute!

What a great topic! It is the inspiration for my next interactive, student-contributions bulletin board at my K-6 library, “Home Sweet Home: write something about a home in a book you’ve read.” I can’t wait to see what the students add to the board!

I’d love to see that, too! Keep me posted? (My email is just my first name @ keirgraff.com)

What a wonderful idea for a top ten list! Many of my favorites are on this list, and a few others are on my to-read list. In fact, I just finished re-reading The Wind in the Willows. I love the description of Mr. Badger’s home, and I also love when Rat and Mole rediscover Mole’s home and make it cozy again. Such a charming and poetic book!

Reblogged this on Notes from An Alien and commented:

Today’s re-blog is something certain aspiring writers might be able to use to envision who they might want to write for…

I would love you to write more Top 10 lists! Dogs, Bears, Cars, Trees . . . This one is brilliant!