September

03

September

03

Tags

A Silver Lining: How Being Deaf Informs My Work by Cece Bell

When I was a kid, I was too anxious to ask the librarian at our local library for a library card. I dreaded those kinds of interactions, the ones that meant I would have to lip-read an adult I didn’t know and maybe make an embarrassing mistake. So I would walk the four blocks to the library several times a week, pull books down off the shelf, look at them for a while, and then re-shelve them and go home. I rarely looked at anything with a lot of text—I was expected home within a reasonable amount of time, which I believed was never enough time to read a whole book—so why commit to reading something that might be checked out when I returned to finish it?

So I’d look at picture books and early readers and comic books in the dim, cool library, particularly the collection of Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo that no one was allowed to check out, as it was almost as big as I was. I’d pore over those gorgeously rendered comics, trying to figure out how they were made and how I could replicate their beauty. I was also obsessed with Ezra Jack Keats’ The Snowy Day, marveling at how Keats combined paints and prints and bits of paper to create all those perfectly designed pages of absolute art.

The walks back home were filled with visions of the pictures I’d seen; with happiness in knowing I’d get to visit those pictures again and again; and with anticipation as I mapped out how I would create pictures just like them.

In a way, then, my resistance to getting a library card, so much tied up in my deafness, was the beginning of my path towards becoming an illustrator. And in spite of not doing much reading in the library, I somehow became a writer, too. My writing also evolved out of a desire to make art: I started writing because I wanted to draw pictures to go with words, just like McCay and Keats had done. I am now what you’d call an author/illustrator, but I’ve always liked the term storyteller. A storyteller who uses both words and pictures to tell stories.

Being deaf not only informed my path to becoming a storyteller, but it has informed my storytelling itself. Recently, I was going through my “papers” so that I could donate a good bit of them to my alma mater, the College of William and Mary. The sorting and organizing put me in a contemplative mood about my career and the books I’ve made in the past twenty years. I’ve long thought that being deaf might have an impact on my work, and seeing all my work at once verified that belief.

Being deaf not only informed my path to becoming a storyteller, but it has informed my storytelling itself. Recently, I was going through my “papers” so that I could donate a good bit of them to my alma mater, the College of William and Mary. The sorting and organizing put me in a contemplative mood about my career and the books I’ve made in the past twenty years. I’ve long thought that being deaf might have an impact on my work, and seeing all my work at once verified that belief.

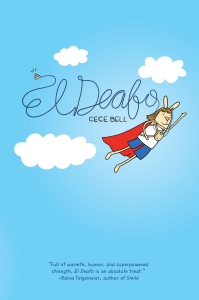

As I pored through the materials for each individual book, I was reminded of the unique ways my deafness might have informed each one. Obviously my deafness had a huge impact on my autobiographical graphic novel, El Deafo, which chronicles my hearing loss and my early years as the only deaf kid in a school filled with kids who could hear. But my deafness flits around the edges of all my books; I’ve been “writing what I know” all along.

Take, for example, my personal favorite of all my books, the picture book Bee-Wigged. If El Deafo is my direct autobiography, Bee-Wigged is my indirect one. Oddly enough, I didn’t realize this as I was working on it; only after it had been out for a while did I see the similarities between Jerry Bee’s story and my own. Jerry Bee is a giant bee whose dream is to be friends with the very people who fear him. Jerry is not a proper bee, but an enormous, child-sized one, and who in their right mind would want to befriend an enormous, child-sized bee? As a kid, my deafness made me feel like I wasn’t quite right—I wasn’t a proper bee—and I worried that people would avoid me because I was “different.” Just like Jerry does in Bee-Wigged, I made an extra effort to be “helpful, funny, artistic, and generous,” figuring that over-compensating on these character traits would help me surpass any perceived differences and help me make friends. (Jerry and I were right. It works!)

Then there’s Rabbit and Robot: The Sleepover. It was librarian Betsy Bird who showed me that the anxious, easily confused Rabbit might represent me, while his friend, the ever-helpful Robot, might represent the Phonic Ear—my giant hearing aid that helped me navigate so many years of school.

Even the sequel to that book, Rabbit and Robot and Ribbit, has connections to my deafness that I did not see until the book was completed. In this one, Rabbit is jealous of Robot’s new friendship with Ribbit, made doubly frustrating because Rabbit can’t understand anything Ribbit says, while Robot can. This only multiplies Rabbit’s feeling of being left out, a feeling that continues to haunt me even through adulthood. It isn’t easy lip-reading more than one person in a group!

Like Rabbit and Robot and Ribbit, so many of my books are about the difficulties that often occur when we try to communicate with others. More specifically, the difficulties that occur when we mis-communicate, and the confusion that ensues. I’m a good lip-reader, but I make plenty of mistakes. And plenty of those mistakes turn out to be hilarious (adults reading this essay: ask me to tell you my OBGYN story sometime). There’s all the who’s-on-first grammatical shenanigans in I Yam a Donkey (and the homonym shenanigans to come in the follow-up You Loves Ewe). And there are plenty of hilarious misunderstandings that develop in my latest, the graphic early reader Chick and Brain: Smell My Foot, due to Chick’s insistence on good manners at all costs.

Deafness can be challenging, but it has some real silver linings, too: I can silence the whining of children and the yipping of tiny dogs whenever I want. But one of the silver-iest of those linings is that my deafness has made me a better author and illustrator—a better storyteller. One who is now able to check out books from the library by my favorite storytellers, because I eventually did make peace with my giant bee-ness. Then I turned on my Jerry Bee charm and asked a librarian for a library card of my own.

Cece Bell is the author-illustrator of many books for young readers, including the Theodor Seuss Geisel Honor Book Rabbit and Robot: The Sleepover and the Newbery Honor Book El Deafo. Her newest book Chick and Brain: Smell My Foot!, a graphic reader, publishes September 3rd. Cece Bell lives in Virginia with her family.

I just book-talked EL DEAFO today with high school seniors. Several had already read it. Thanks for this post that adds even more depth to your amazing story.

So interesting to hear the story behind how you became an author and an illustrator. (And, I’m glad that you finally got a library card!) Thank you for sharing!

Cece, this is a wonderful post, which I look forward to sharing. Thanks for the beautiful work you do!! (and yes, I will ask you about that OB/GYN story the next time I see you, lol!)

You will laugh, Jen Bryant!!!

Thank you for sharing your journey. Your books will touch many lives.

Love this. Thank you for sharing Cece!

Cece, you are a treasure. Yes, you are in your books! My veryfaveorite PB of yours is I YAM A DONKEY. It made me duh so hard that myhybs and I read it aloud and acted it out! I was lucky enough it see you this year’s Nerdcamp MI, too. Ty for sharing how your early reading experiences made you the writer you are. Kids will be fascinated about this.

What a wonderful post! In my household, we love all of your books, but Bee-Wigged holds a special place in our hearts (maybe because it was the first of your books that we bought, but probably because of the guinea pig).