January

25

January

25

Tags

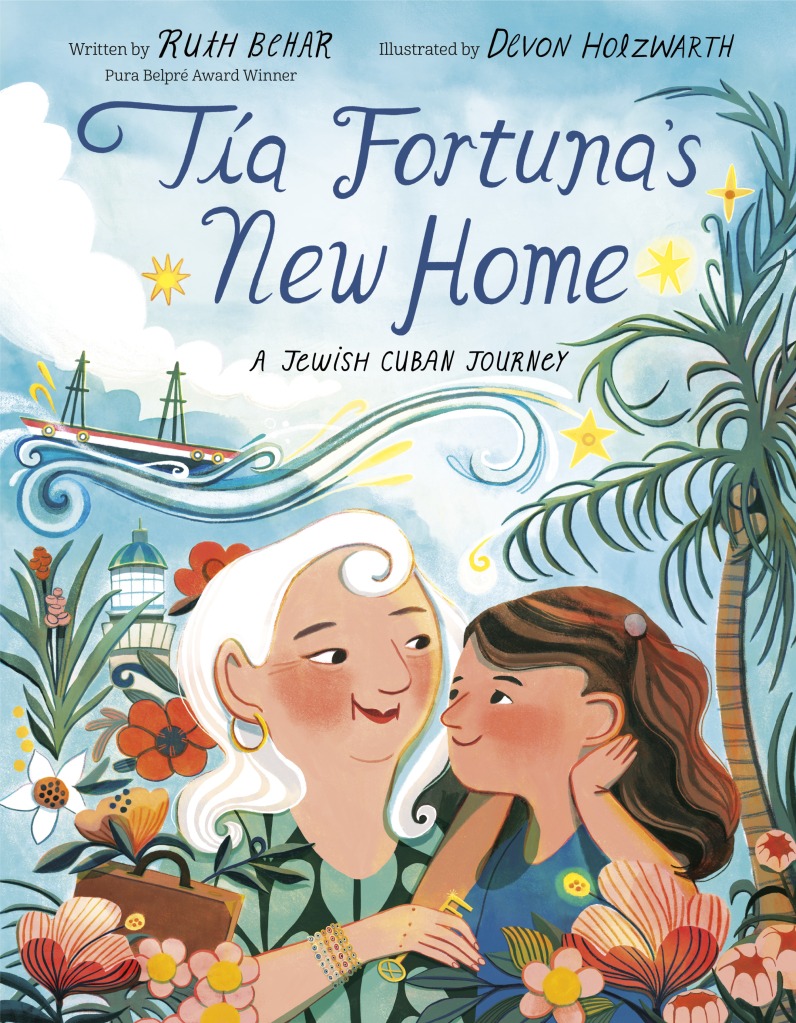

Gently Passing on a Heritage by Ruth Behar

When I sat down to write Tía Fortuna’s New Home, I thought it would be easy to write a picture book about my Sephardic cultural heritage. But it turned out to be incredibly difficult.

There are many layers of drama and displacement in Sephardic history that I wanted to put in the story without overwhelming it. The Sephardim descend from Jews who lived for centuries in Spain (Sefarad in Hebrew) but were expelled in 1492 for their religious beliefs. They dispersed to many countries, including Turkey, where my ancestors settled. In the early twentieth century, many Sephardim left for the United States, Israel, and Latin America. Some settled in Cuba, including my family, only to start a new life yet again in New York and Miami. Throughout these migrations, they never forgot their nostalgia for Spain, continuing to speak an old Spanish dialect, or Ladino, as it came to be known.

My Sephardic heritage comes from my father’s side, but I grew up closest to my mother’s parents, Ashkenazi Jews from Poland and Russia. They had also settled in Cuba, merging their Yiddish traditions with Cuban traditions. They would joke that I was like my father’s family because of my dark eyes, curly hair, and strong will—a Sephardic temperament, they thought. I only picked up bits and pieces of that mysterious Sephardic heritage. I knew a few words in Ladino and I loved my abuela’s borekas, turnovers filled with potatoes and cheese, or spinach and cheese, a traditional Sephardic food.

I found my way into the magic of the story, and out of the quagmire of being the anthropologist trying to explain everything, when my two main characters, Tía Fortuna and her niece Estrella, took form and came alive on the page. Tía Fortuna was inspired by a real-life Sephardic aunt in Miami Beach who serves me borekas whenever I visit. The character of Estrella is inspired by my own childhood memories: happy to be with my elders, listening to their stories and never getting bored. It occurred to me, what if Tía Fortuna is an elder, a Sephardic Jew who had to leave one home in Cuba and now has to leave another home in Miami Beach? And what if Estrella comes to help her auntie pack and say goodbye to her home by the sea? And what if Tía Fortuna passes on something of her heritage to Estrella?

Little by little, the story grew. I knew from the start that the story would be set in Miami Beach. I’ve loved that part of the world since I was a child. After resettling in New York, my parents missed the tropical beauty of Cuba. We visited Miami Beach for a week one summer and were enchanted by the sea, the warm breezes, and the palm trees.

In recent years I’ve been spending a lot of time in Miami Beach and nearby Surfside. That’s how I got to know the Seaway, the real building in which I created a fictional home for Tía Fortuna. I dreamed of living in the Seaway and saw a little cottage there, like a dollhouse, that stirred my imagination. Then I learned that the Seaway was going to be demolished, like so many other humble beachside buildings, to build a luxury hotel. I decided it would be her casita at the Seaway that Tía Fortuna would have to part with. Her ancestors had lost their homes to expulsion, war, revolution. She would lose her home to gentrification.

Little Estrella is saddened, but Tía Fortuna encourages her to enjoy their last day at the Seaway and not think about mañana. Tía Fortuna’s acceptance of change lifts Estrella’s spirits. Still, her auntie wears lucky eye bracelets and keeps hamsas around, whispering prayers for mazal bueno—good luck. Tía Fortuna makes borekas for Estrella, filled with potatoes and cheese and also with esperanza, reminding her that her ancestors found hope wherever they went. In this way, she gently passes on her heritage to her niece.

After Tía Fortuna closes the door to her casita and pockets the key, she says goodbye to the palm trees. They whisper back adiós, adiós, adiós, for the world is a magical place. Estrella’s mother arrives and they drive to Tía Fortuna’s new home . . . which turns out to be what we call a home, often referred to as an assisted living facility. Again, Tía Fortuna insists on finding hope and accepting a new beginning. Though now far from the sea, there are banyan trees that she hugs and that whisper back, hola, hola, hola. And the butterflies flutter. As Estrella excitedly asks when she can visit again, Tía Fortuna whispers, “Mashallah, God willing.” So my abuela and abuelo would say, never assuming another day was a given, treating each day as a blessing.

Ruth Behar is the author of Lucky Broken Girl and Letters from Cuba. Her debut picture book, Tía Fortuna’s New Home: A Jewish Cuban Journey, is also available in Spanish as El nuevo hogar de Tía Fortuna: Una historia judía-cubana (translated by Yanitzia Canetti). She lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Ruth Behar is the author of Lucky Broken Girl and Letters from Cuba. Her debut picture book, Tía Fortuna’s New Home: A Jewish Cuban Journey, is also available in Spanish as El nuevo hogar de Tía Fortuna: Una historia judía-cubana (translated by Yanitzia Canetti). She lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Reblogged this on NEW BLOG HERE >> https:/BOOKS.ESLARN-NET.DE.

Thanks you for sharing the story behind this precious story. I look forward to reading it soon.